More than half of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are Christians.* Only one Indigenous language in Australia, Kriol, has a full Bible translation.

Let that sink in.

The vast majority of First Nations brothers and sisters in Christ do not have God’s word in their heart language. That’s a precious gift so many of us simply take for granted. While about 22 Indigenous languages have, at least, one complete Old or New Testament book, there are about 120 Indigenous languages spoken in Australia today.

Bridging this gap in access to Scripture is why Bible Society Australia remains intent on backing translations in Indigenous languages. Like you, we see the importance of this to identity and culture, as well as the eternal value of Opening The Bible to all people.

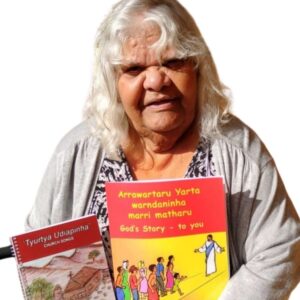

Recently, the Adnyamathanha people – from the area now known as the northern Flinders Ranges in South Australia – had a breakthrough. Not only was a hymn book of church songs published in Adnyamathanha for the first time (‘Tyurtya Udiapinha’) but so was a children’s book and CD, God’s Story for the Outback.

Critical to both was sole translator Lily Neville. After surprising herself years ago about how she could translate the Lord’s Prayer into her heart language, Lily hopes to inspire others to translate more and more.

“Once you put your mind to it, you can really translate anything into Adnyamathanha,” says Lily, who grew up speaking it with her parents. A regular at church “from Sunday School up”, Lily feels a sense of pride about being able to put Christian resources into her people’s own words.

“I didn’t think it would be easy like that; well, I find it easy anyway to translate anything. I do my best. I travel by the grace of the Lord and that’s how I’m getting that work done. I believe that by faith you can do anything, especially keeping the language going.”

“It’s very important to me. I don’t want to lose the Adnyamathanha language.”

According to the 2006 Census, only 107 people spoke Adnyamathanha at home. But the number of First Peoples who identify as Adnyamathanha is much higher. Lily hopes God’s Story for the Outback is one positive way for the next generation to do two things at once – nurture the words of Lily’s heart language, and also be changed by the words of God.

“I would like them to get the knowledge and understanding and pleasure out of reading this book,” Lily says of a book about “Jesus’ story”.

“I really was excited to get this published.”

“Now, my little ones – the grand kids – can read it and learn. I know there are a couple of them on the road to doing the Adnyamathanha language. I’m thinking positive that they will get involved in this.”

“I believe that by faith you can do anything, especially keeping the language going.”

Having done the song book and kids book, Lily is confident in her skills, something Tom Little – an elder of the Bindjareb/Bibbulmun people – has also developed into a powerful tool for God’s work.

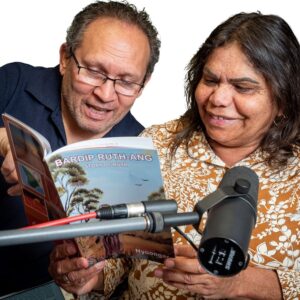

Tom Little’s mum and his aunts told him to help them translate the Bible into their heart language. He knew what the right answer was.

“When they gang up on you and tell you to jump, you only ask, ‘How high?’” says Little with serious jest, thinking back to how he first became involved with the Nyoongar Bible Translation Committee around 1995. A few years earlier, Little’s mother and aunts became founding members of the committee helping to keep alive the Nyoongar language (originating from south-west Western Australia).

“They said to me, ‘You’ve got to come to help us to do this’”, says Little. “I said, ‘Hang on, you speak the language better than I do.’ They said, ‘Yeah, but you remember better than we do.’”

Little says that since God’s word began to be translated into Nyoongar, two books have been completed. The first was the Gospel of Luke, which took about 20 years, due to the “exhaustive process” of language work that “became the template for later translations.” The second biblical Nyoongar text was the Old Testament book of Ruth, which Little completed single-handedly last year – in just four months. “I was extremely lucky that about 98 per cent of the language I needed for Ruth was already embedded in Luke,” Little says.

But shared words were not the reason Ruth was picked. “It was logical to do Ruth next because I grew up in a household of strong-willed and faith-filled women. My mother and my aunts are all Christians.”

The Nyoongar translation of the book of Ruth is “absolutely” a tribute to these women, says Little. “I made it perfectly clear to them that the reason I chose Ruth was because of the example that they had set me.”

Even with the increased rate of Ruth’s completion compared with Luke, Little still is not sure the whole Bible can be translated into Nyoongar during his lifetime. He’s keen to give it a go, though, with ongoing support from Bible Society Australia, its Remote and Indigenous Ministry Support team, and the vital help of experts such as Rev. Dr. John Harris, Bible Society’s translation consultant.

Language is often the barrier keeping our First Nations peoples from Opening The Bible. That’s why Indigenous communities around Australia are proactively helping with translation, so as to speed the work of receiving God’s word in their heart languages. Pitjantjatjara translator, Katrina, says: “We are translating it so others can have a true understanding of the Scriptures.”

More than 20 projects this year need support so we can reach remote communities. It’s part of Bible Society’s special ask for 200,000 Scripture resources to Open The Bible at Home in 2021. Please give Australians the opportunity to do this, and pray as hearts are prepared to receive God’s abiding love.

For the entire law is fulfilled in keeping this one command: ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.’ Galatians 5:14 (NIV)

* 2016 Australian Census